Is fear of change or loss aversion impacting hiring?

After seeing Mark Gilroy’s fabulous YouTube video about change, (not the one where he’s singing that song 😉 ), I wanted to know more and how recruiters can influence change.

A self-confessed professional psychology geek, Mark & I had a fascinating conversation that will help recruiters & hiring leaders partner better! We talked about:

- let’s stop pathologising change and reframe change in the right language

- the pandemic showing us that change isn’t hard!

- change accompanied by loss is the real issue. Loss aversion is big!

- rational thinking vs. primal more emotional responses

- winning hiring manager conversations by talking about loss aversion

- sunk cost fallacy and the Ikea effect, and how this impact recruitment remorse

- choosing your language around change with care

- measuring optimism, energy, and level of fault-finding at the start

Grab a cuppa, pen and paper and settle in! ✍🏻

Full Transcript: Mark Gilroy – Averting Loss Aversion In Hiring

Mark Gilroy, welcome to The Hiring Partner Perspective podcast proudly supported by the beautiful people at WORQDRIVE. I am so excited to talk to you today.

Mark Gilroy 0:58

Hi, Katrina, thank you so much for having me.

Katrina Collier 1:00

Oh, it’s good. We’re trying not to sing. We do really want to go ch ch changes, don’t we?

Mark Gilroy 1:05

I mean, there’s so many songs about change that we could get into.

Katrina Collier 1:08

I know that we could just sing the whole podcast. But thankfully, regular listeners, you’ll know that that’s not wise. So Mark, can you tell people who amazingly don’t know who you are? What it is that you do?

Mark Gilroy 1:22

Oh that’s kind. I’m a professional psychology geek is what I usually say. It’s quite a difficult thing to explain. But if people go that, I know that I’m incredibly geeky about the world of psychology, that usually covers it. So if anyone wants to get in touch and geek out about anything psychology based, then you know where to find me. But aside from that, I’m a facilitator. I’m an executive coach. Officially, I am also Managing Director of a company called TMSDI and we work with HR and L&D professionals, and we offer training and a variety of psychometric tools that are used all over the world.

Katrina Collier 1:54

So you’re not going to analyze me now, that would be really scary. Let’s not go there

Mark Gilroy 1:59

I will be, but I won’t be telling you anything about it. That’s just exactly what we do all day long.

Katrina Collier 2:05

You’ll be doing that in that beautiful British way, where it’s a bit passive aggressive, but doing it on the inside, not sharing it without a huff and a puff.

Mark Gilroy 2:12

If hear me say that’s interesting, and start making notes down here, then you’ll know that there’s something going,

Katrina Collier 2:16

I’m screwed. So I saw because of course, you’re now a famous YouTuber, that you done to that brilliant YouTube video about change. And I think the thing that got to me or with it was the sort of the fear of loss. But can we delve into this? So what is it? You know, if I’ve got recruiters who are wanting to get hiring managers to join them and partner in change? What is the problem? Why are we so scared of it? What’s the big deal?

Mark Gilroy 2:44

It’s weird, isn’t it? If you Google, change it and look into it, most people are searching for things like ‘why is change so hard? or ‘why do some people that I work with seem to massively resist change?’ And I think that in itself is really interesting that people are looking to almost pathologise it and try and find a way around, you know, to sell change to people or to influence people who for some reason are stuck, and won’t listen to the need for change.

And, and so from my perspective, from a, and I guess, I identify quite strongly as a psycholinguist. So for me, language is super, super important. And actually having a really good way of either reframing, or repositioning change using the right language is one fantastic way. And we can talk more about that later on in our discussion about sort of ways to help address, you know, the perception that some people might be stuck around, you know, negotiating around change.

Katrina Collier 3:38

Ooh, I like that the perception that some people are stuck,

Mark Gilroy 3:43

Because it is, we’re all about perceptions, aren’t we? And we’re all about, and our perceptions are a feature of our past and all of our experiences they have to be, you know, we will worry about a combination of all those things.

Katrina Collier 3:57

And when you think about the perception that companies had, that nobody could work from home that got blasted out of the water, you know, it’s crazy to think we’re having this conversation in 2022. But still, there’s this resistance.

Mark Gilroy 4:10

And that’s such a great example. Because I think, for me, I always want to challenge that assumption that change is hard. If anything has been demonstrated over the last couple of years, change isn’t hard, like people can change very quickly, and things can change incredibly quickly. And especially things that, you know, maybe we thought might take a little bit longer than they did.

I remember speaking to somebody in the height of the pandemic in 2020. And they were saying that pre-pandemic, they had estimated that in order to get their entire workforce working from home, it will take them about two years to manage and then deliver on that project. They did it in two weeks.

Katrina Collier 4:48

What on earth were they going to do for two years? Here’s a laptop, access to the Wi Fi off you go… Okay, I’m being very blase because of course, that means they are all knowledge workers

Mark Gilroy 4:59

It’s interesting, isn’t it? You know, what, what on earth were they going to do for two years? And the, my assumption would be, there’d be a lot of stakeholder engagement, there’d be a lot of laying the groundwork, there’d be a lot of strategy sessions, there’d be a lot of fault finding, I suspect.

Katrina Collier 5:14

Yeah. And ‘Oh gosh, I’m not gonna be able to trust my people, if they’re working at home, I’m going to have to monitoring software on their computers.’ By the way, anyone that’s done that, God help you recruiting in the future.

Mark Gilroy 5:26

It’s still mad that that even happened, isn’t it? Maybe?

Katrina Collier 5:28

Yeah, or open Zoom windows.

Mark Gilroy 5:33

Just as unusual virtual zoo opened up in certain organizations? Yeah, it is. I think, for me, what that’s probably the the key thing that’s changed is that people just realized that you couldn’t analyze every possible thing that could go wrong, or assess every possible risk, because it just needed to happen. And so and so something’s shifted there.

So there’s probably some really important lessons that people can take away from how various organizations were able to do that quickly, whilst also making people feel safe. And that it wasn’t entirely chaotic. Because change can also feel like that.

Katrina Collier 6:10

Yeah, I found it quite interesting. You think of like traditional call centers, I had a couple of conversations with insurance companies, as I’m sure many people did, when all their flights and everything were canceled, but that how happy they sounded, because, and also, you could hear them and they were a bit more relaxed, and you could have a longer conversation.

So actually, one actually upsold me because they were so relaxed, rather than in that very loud environment, with lots of people around them. So I found it quite interesting. Yeah, big change, big change. We weren’t gonna talk about that. But here we are. The joy of the podcast.

Sorry, the podcast.

Mark Gilroy 6:42

And, you know, you referenced the video that I made. And so the general video was that do not change isn’t hard. It happens all the time, even pre-pandemic, you know, there were there, you know, people get married, they get divorced, the different items appear on a coffee shop menu, and then they disappear agai. Things change all the time, and people are generally okay with it. The issue tends to be when that change comes along with a feeling of loss.

Katrina Collier 7:12

That was the bit that really stood out to me, was that ‘oooh so we have to work out what they’re scared they’re going to lose?’

Mark Gilroy 7:20

Absolutely. And that’s the key to it. So this comes from the work of researcher, author, Nobel Prize winner called Daniel Kahneman, and less famously, his colleague, Amos Tversky. And they did some really interesting research around the idea of mental accounting, the idea of value and perceived value. And what they found is that pretty consistently, people behave very predictably.

And very safely if a change is presented to them as a gain. So in their case, it was often you know, how much money would you like to win? Would you prefer this scenario where you could win a certain amount of money? Or would you prefer this scenario where you could win even more money, but that might also give you a risk that you might not win anything at all? Most people go with certainty in that situation? Unsurprisingly, right?

Katrina Collier 8:07

Bird the hand?

Mark Gilroy 8:08

Bird in the hand. Absolutely. Of course, some people are just happy to go well actually I came in with nothing, I’m happy to leave nothing, and they’ll go for the big risk, which says a lot about their approach to change and risk. And they went on to then find that when the value proposition was presented as a loss, in other words, would you rather lose this amount of money?

And know that you’re going to be losing this amount of money? Or would you rather lose this amount of money with a percentage chance of not losing anything at all, people actually behave very differently in that scenario very consistently.

And they put it down to this, this idea of, of positioning something as loss, suddenly, almost, you short circuit that logical rational thinking, and you get to something a bit more primal bit more emotional. Yeah. And that makes sense, doesn’t it? Intuitively, that makes sense.

Katrina Collier 9:01

So what do most people choose, then? Of those? Do they just take that and go, I’m not losing anything?

Mark Gilroy 9:08

Well, there is that I’d rather not have any of those options, obviously, for things, people behave in a much more risky way. So they will actually they will risk losing a much larger sum of money, if there’s a small percentage, they don’t lose anything at all.

So that’s, you know, that pretty significant. So people switch on the switch to this, you know, incredibly risky behavior and much less predictable, much less rational behavior. And that that has to enter a conversation about change, because so often, change and loss go together either in reality, or in a perceived way, that’s really important that we acknowledge that.

Katrina Collier 9:49

Bringing it back to recruiters. I don’t feel we talked enough about you know, the hiring manager is after this unicorn, as we like to call them you know, this person, there’s one person on the planet that can do the job, rather than being realistic, and they don’t think about the loss of they can’t deliver the project, or the loss of profitability, while they’re waiting to fill this role, etc.

So I guess that’s possibly an angle that more recruiters need to take. So what are you prepared to lose some of the requirements on the job description, or some profit? Interesting, and you’ve only been talking for nine minutes, and I’m only like ca-ching! Lightbulb

Mark Gilroy 10:34

I think that would be make a huge shift in the way people start to think about recruitment. Because it’s so rarely part of the conversation, isn’t it? What are you prepared to lose? And how will we know? You know, when will we find the point where we get actually, that’s the, that’s the point at which we’re prepared to lose X amount. Beyond that, that’s too much.

Ahead of that, that’s fine. It’s quite, it’s quite an unusual thing, because that is a different type of loss, loss of face, you know, saying actually, I’m prepared to lose the company a particular amount of money.

Katrina Collier 11:04

I can’t deliver that project because I can’t hire that person. I’m after a unicorn. Oooh I’m loving this.

Loss Aversion

Mark Gilroy 11:11

Loss Aversion really important. Unconscious bias. Again, we weren’t going to talk about this today, but loss aversion is a really big driver, that people will either stick their heads in the sand, or they will actively make sort of patterns of behavior that reduce their perceived or actual losses. That’s a really, really heavy unconscious bias that we all walk around with.

Katrina Collier 11:35

Can you give me an example?

Mark Gilroy 11:38

Okay, so an example of this might be could be a sunk cost fallacy. Okay. So here’s an example of that. And this is, this is tricky. You might tell from my accent, I’m from the north of England, and we haven’t been reputation in the north of being quite, you know, quite..

Katrina Collier 11:58

Tight.

Mark Gilroy 11:58

Tight. Thank you. That’s the label I was looking for.

Katrina Collier 12:04

Well as an Australian, I can offend all the English, it’s fine.

Mark Gilroy 12:07

So okay. All you can eat buffet. I paid my money. I’m going to eat as much as I possibly can because I’ve sunk that cost, even if it makes me feel ill for a couple of days. So that is an example of a sunk cost fallacy. And I actually that happened to me. Yeah, I remember what they called that world buffets, where you could have like, a carvery and Chinese meal and, and some babbons on the side. And I, I really did make myself very poorly, because I was I was absolutely said that I was going to get my money worth from that particular scenario. And it was just a classic one of, you know, I’ve lost this much so therefore.

Another example could be, let’s say you’ve bought concert tickets to see your favorite band, and when you set off, there’s a terrific snowstorm that actually might be really dangerous to come head off in. But that loss aversion that sunk cost fallacy in this particular case, would mean that most people would try and try and get there because they might not get their money back. And they’ve already committed to putting aside the time and putting aside the money of having a good evening out together, watching their favorite band that actually they might run the risk of having an accident or not getting there.

Katrina Collier 13:21

Do you think that’s why some managers hang on to team members that they’ve recently hired that aren’t great? Because they’re like, oh, loss of faith, or…

Mark Gilroy 13:31

Sunk cost fallacy is a really good example of that. Yeah, absolutely. It’s my decision, I’ve owned it, I’ve made it I don’t want to lose face, I don’t want to lose the amount of effort and and resources that I’ve put into developing this person, even if they’re not quite the right fit.

Katrina Collier 13:49

I don’t think I’ve well, I’m not a psychology geek, because I have just haven’t, considering the five decades I’ve been on the planet haven’t come across this before, as a sort of a bias that, actually I think is at play a lot. I think it’s, you know, within recruitment, I always think it’s like gap bias or, you know, didn’t go to my school bias or class bias or, and then all of the others, ethnicity, gender, etc. I’ve never thought about loss. Gosh, it’s huge.

Mark Gilroy 14:19

It’s a really big arena. And I’m going to just hold it to the to the web cam, and, this is audio only but, if you can see this, this has been my weekend project, I built some adult Lego. I’m obviously at the age now

Katrina Collier 14:32

I think it might be Batman.

Mark Gilroy 14:33

It is a Batman head.

Katrina Collier 14:34

He is waving it around quite a lot. It’s a Batman head. When did Lego becomes so complicated?

Mark Gilroy 14:41

Oh, right. I know. You can call it adult Lego. Apparently it is they come in a very adult black box rather than a very brightly coloured one.

Katrina Collier 14:50

Does that mean they don’t hurt so much when you step on them in your bare feet?

Mark Gilroy 14:56

I think that’s the case. I think that is the case. So that was to remind me have an example of what you were just talking about where you know, where you’ve got a, you know, a hire, you’ve made a hire, and it’s maybe not quite the right fit. There’s something called the IKEA effect. And I’ll send you the link to some of this research. So you can add it to the show notes if you wanted to. So the IKEA effect follows that. A number of researchers discovered that, and again, this is back to value.

When two groups were given a Lego set to build, one group was given the instructions and a group of pieces. The other group were given the prebuilt toy or car or whatever it was the model, and told to play with it for a while, and then asked to come up with a number that they would pay for it to keep it. Consistently, significantly, you can see where this is going, right? The group that built the set from scratch, would pay substantially more, I think, I think the research suggested four times more,

Katrina Collier 15:58

Because of the energy they’d put into creating it, and building it themselves.

Mark Gilroy 16:02

Yeah, they literally built it themselves, they put something of themselves into it, and therefore they wanted that value back.

Katrina Collier 16:08

That really does explain why people hang on to bad hires. That’s really interesting.

Mark Gilroy 16:16

The IKEA effect they call it because the same would be true if you know if you had a piece of furniture that you built yourself that people value it more. Yeah, they hold on to it for longer, certainly

Katrina Collier 16:25

interesting. Okay, so going back to our ch-ch-changes, we’re not going to sing David Bowie, we’ve realised it’s too challenging.

Mark Gilroy 16:34

Let’s turn to face to change, shall we?. Yeah.

Katrina Collier 16:38

So what can recruiters do, they’ve come up against a hiring manager who is being ridiculous. Are there any sort of tips or tricks? Or what can they do to kind of negotiate around this fear of loss as perhaps it is rather than fear of change?

Mark Gilroy 16:52

Yeah, what again, if you Google around any of this stuff, you probably wouldn’t take too long before you come across a model by an author called Kubler Ross, which is around grief, I would challenge that, I’d say stay away from that for now. And I think it’s a helpful tool helpful model. But this is very much around actually responding to grief in a particular way. And I would, I would argue, loss and grief, don’t always go hand in hand, I can know something but not have to grieve,

Katrina Collier 17:19

I just want them to lose some of the ridiculous things on the job description. And lose their opinion of oh, we can’t have somebody working from home, or we can’t have this or we can’t have that. Not necessarily grief.

Mark Gilroy 17:31

You might see, you might see some of those behaviors wound together. Things like shock and denial and anger. Yeah, of course. But actually, this idea that there’s a logical flow that people go through when they’re experiencing change, I’ve never seen happening in reality. And I think it’s well worth just holding that up and saying, you know, that’s a model that works for a particular scenario that doesn’t automatically work for change.

So there are all kinds of tools models that are really helpful. And of course, I’m going to come back to language. And I think it’s really good to really consider the language that we’re using to talk about any kind of change. Because typically, the language about change is really tricky. You hear a lot about driving change, or managing change. And that almost gives this kind of idea that it’s possible for one person or a group of people to sit at the wheel of whatever this change is, and kind of just steer it and do something with that or press the accelerator.

Katrina Collier 18:28

It sounds heavy to me, like it’s effort, because I’m quite fine with change. It sounds like, Oh, this is going to be hard work,

Mark Gilroy 18:38

Doesn’t it? Yeah, it often puts the onus on one person or a group of people, if they’re, you know, leaders or change agents, or whatever that language might be, it seems, it gives the implication that there’s, yeah, there’s, there’s a lot of weight that needs to be shifted.

Katrina Collier 18:54

I can imagine those that don’t like change, avoiding anybody with job title change agent. You can imagine them like hiding. Ooh God here, they come down the corridor, I’m running into the loo

Mark Gilroy 19:03

Waving their big change flag.

Katrina Collier 19:09

Ah it doesn’t quite work when you think about remote working. But you know, back in the day, when we’re in the office, I could totally see people doing that.

Mark Gilroy 19:15

And not wanting to get too navel gazing into the language, because I will, I will do it. If you don’t stop, you know that that whole piece of dynamics of change encourages the idea that change is something that is done to people. Yeah, rather than something that people have an active part in shaping and happen.

Going back to the analogy of the car, I think the reality of a lot of changes that it doesn’t happen at the driving the driving seat where the wheel, it actually happens in the engine, yeah, all the energy comes from there. And so the best way to to get into talking about change and thinking about change and and making change happen is to find where the energy is and start there. Because that is what will create the propulsion The energy that’s that’s needed to, to move something forward or make that change happen.

Katrina Collier 20:05

And I assume that No, I shouldn’t assume, I’ll just assume anyway, because I’m halfway through that sentence, it often comes from pain, that we have a problem, you know, we can’t hire or we’re losing stuff. I mean, that’s certainly what’s going on in this market. The great reassessment resignation, whatever buzzword you’d like to call it, but that would be a pain point driving the energy of change, I guess.

Mark Gilroy 20:28

Yeah, can you say some more about that I’m interested, I’m interested to know more about. So

Katrina Collier 20:31

Just that. I mean, really, across the board, across the world, from having over fired in 2020, theu are now over hiring in 2021/2022. And they’re really, companies are really seriously struggling. So it’s like, where they may have been able to pick and choose before now it’s literally like, now we have to accept, we need to open the net more, we need to reduce some of our biases, that it would be coming from pain that need to change in many respects.

But then, of course, if you balance it with what they’ll lose, if they don’t hire. Also, what you’re talking about reminds me so much of the facilitation that I’ve started doing, which is all around design thinking. So you actually get people in a room, collaboratively sharing, like what their pain points are, and then democratically voting and then creating solutions together. It’s quite nice, because then the resistance drops, as well, which is quite interesting. Yes, it’s, it’s that. Yeah,

Mark Gilroy 21:32

I think that’s really personal. That idea of, you know, change coming from a place of pain. I think that that that is for a lot of people that that’s the reality and change, and that that creates a lot of urgency. You know

Katrina Collier 21:44

Can the energy come from somewhere else? Does it always have to be negative?

Mark Gilroy 21:47

Yeah, often, it’s about harnessing the emotion. So you know, that energy within the car analogy we were talking about a second ago, that can come from anywhere, it can come from logic and reason. And in fact, and you know, the, the work of somebody like Kotter, who talked about change a lot.

And he’s, you know, wrote a great book about penguins, and melting icebergs, which I can recommend to check it out. But he talks about creating a compelling argument. And then, and then recruiting people who will help you sell the idea to the rest of the team, or the business or, or whoever it is that you’re looking to convince, and, in that case, the emotion, what, in a sense, is pain, but it’s also a bit of fear. And it’s a bit of urgency. But there’s also some idea of selling the optimism of the future state that you’re moving towards. And that can be as compelling.

Katrina Collier 22:32

So that’s totally something that recruiters can do in the intake strategy session that they far too often don’t get, but they need to demand. Which is Chapter 5 of my book, which I crowd sourced. it’s not all me.

Where, they’re gathering that data and that evidence, and almost that pool of supporters as well, if you will, to go into those meetings and saying, like, this is the state at play, this is why we need to make this change. This is why things will be better in the future, if we do this. So they can tell us spin it to the positive

Mark Gilroy 23:00

Definitely, just just coming back to what you were saying about things feeling heavy, I think that’s also really common sense from a lot of teams, from a lot of leaders. And, and there’s a really good reason behind that is, which is that, you know, big things like big changes move really slowly. In a lot of organizations.

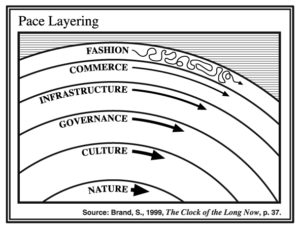

There’s a wonderful book, which is quite introspective, a bit of a philosophical book called The Clock of the Long Now. It’s by an author called Stewart Brand. And he he credits among other people, Brian Eno, the record producer, Brian Eno with this idea of, of pace layers. So if you imagine a kind of like an onion, and each layer, that onion is a different layer of speed, that change moves through. He likens that to tiers of society that move at different speeds.

And change needs to kind of go through all of them in order to make something happen. So there’s like a surface layer, which is sort of like fashion and technology. And then that moves super, super quickly changes all the time. And then as you move inwards, those layers kind of become slower. So you’ve got things like commerce and infrastructure, and then governance, and then a more glacial pace, you’ve got things like culture. And then right at the centre, you’ve got the slowest, almost unmoving constant, which is like human nature.

Katrina Collier 24:20

HR processes, we’re gonna be right there.

Mark Gilroy 24:22

Absolutely. And that explains why that is, at the start of the call, we’re talking about, you know, moving from remote working, yeah. That could have taken two years because of that, because of those pace layers would need to have been chunked through at the normal speed. But what the pandemic has done is it’s just cut through a lot of those and as many as you could get through to things like nature, actually quite quickly. And surprise people

Katrina Collier 24:46

the outer layer took control. Here tech goodbye off you go

Mark Gilroy 24:51

Fashion layer and we’re back to Bowie again, aren’t we? Fashion um, but yeah, you take an example any example change you could you can use that as a model to think about what changes you want to effect and how likely is it to move slowly? When is it likely to move fast? And how are we going to help people along with that? I think that’s often where change fails or people struggle with it is because it just takes ages a lot of the time, big things. And people just lose this energy, and I lose the will to make that change happen. And will find reasons that it shouldn’t.

Katrina Collier 25:21

Yeah, and I’ve seen that when I’ve done workshops, and particularly the last one, you know, this is a group of care homes, and they’re just really struggling to hire, you know, combination of the pandemic, and of course, Brexit. And, you know, we come up with these great ideas and solutions, and they’re ready.

And you could just see from so many of them that they’ve been through attempted change before. And they just went ‘Yeah, okay, that’s all well and good, now what?’ And you could just literally see them deflate because they needed the leader, who didn’t do it, to take control. And go, right, we’re gonna push this through, because this is we need to do this, we have 70 vacancies. I think that’s another. So it needs I guess it needs to come from the top as well. And the culture. Complicated, isn’t it?

Mark Gilroy 26:09

It’s so complex, and I guess that’s the reason why there are all these different programmes and tools and models around and people have been writing books for this for years and years and years. Because it’s, it’s about people, you know, effective change is about harnessing the energy of whatever people are going to be responsible for making it happen. And, people are complex.

Katrina Collier 26:29

Yeah. And sometimes they want the change, but then won’t put their hand up and say, I’ll help facilitate it. As well, which is also fascinating. We’re weird lot, aren’t we?

Mark Gilroy 26:41

Um, one of the things that we do at TMS is that we use kind of tools to kind of de personalise it all. You know, we there are all kinds of psychometrics that you can use for change that are really helpful. But there’s one that we that we do that kind of helps people understand the energy we put into assessing risk.

So for example, some people will even hear that word risk, and go ‘Oh brilliant, I’m, I’m in, count me in, I’m excited about something new happening. I’m excited about getting involved with it and rolling up my sleeves and making it happen even.’ Other people will hear that word and go, ‘Oh, no!’ like you just said there ‘We’ve done that before. We did that about three months ago. And it failed spectacularly.

How is it going to be different this time? I need to understand that right from the start, before you’ve got my buy in.’ So you know, having discussions with people around how optimistic they are, for example. How optimistic they are, is, is a is a good starting point. So when we have a measure of that we actually measure that on a on a spectrum, how much energy they’re likely to put into finding fault in people or projects. That’s something that you can measure and have a conversation with people about because, for example, if a team who’s very high on faultfinding, you’re trying to negotiate with them around change and have a conversation with them, you need to start there and address those faults, address any assumptions and critique they may have before they’ll even be on side.

Katrina Collier 28:01

Yeah, I think I’m the risk taker. To a point, I’m not going to jump out of a plane, but yeah, yeah, ’cause that’d be like, Well, if we come across the problem, we’ll work it out. I’m just thinking of like, all the services that I’ve had through my business over the years, it’s changed so many times, it’s nothing like what it was when I started 12 years ago. And I just try something if it doesn’t work, I learn from it and move on.

Mark Gilroy 28:25

And that sense of being able to do that, it’s a bit like a psychological well, that everyone has, and you can draw from that well, and it will give you that energy to do what you’ve done and try something different, and not really care if it works out or not, but just try it for the sake of doing something different. But also it can be those levels in that well can drop and things can drain it. And you need to then top it up somehow.

So we work with teams, and we work with leaders on having those conversations about how do we draw from that? And how do we how do we utilize those resources that we’ve got. Those psychological resources in order to make change happen or to consider risk in a different way? One of my favorite conversations to have is around time and this idea of psychological time, where do you place yourself in time and you’ll know this when people talk to people, some people are very much in the here and now and they they’re very centred, very present, very concerned with just moving forward.

I would say probably even more so since the pandemic people become quite more present focused. Some people just face the past and they they’re nostalgic and sentimental and they want to look back and look at learning lessons from the past and making sure that past is referenced clearly and obviously. Others over in the future, and they they’re awesome almost facing the future, and they place themselves in the future regularly. And for them. The future is a completely clear

Katrina Collier 29:42

A world of possibilities.

Mark Gilroy 29:43

A world of possibilities. Absolutely. And you can shape it right because, you know, you have control over the future, but maybe not so the past. That’s the sort of language that somebody would you would use if they, you know, have a more future focused, you know, psychological timeline

Katrina Collier 29:55

Interesting. So if you had any tips to give our recruiters. Oh, sorry, if you just heard my Spaniel deciding to dig under the table while I’m recording, I love working from home. To be fair, I’ve been doing it for 12 years. So I didn’t actually I was sitting watching all these people complaining going, what’s wrong with you?

Like, yeah, I’d got used to the change already, back when it was actually really hard to work from home. But sort of if you had any final tips that you really wanted to share, or a final nugget, that you just thought, you know, if you if you are facing such resistance, just start here or go read this or any final thoughts

Mark Gilroy 30:34

I’ve got, I’ve got three tips. And we’ll do two L’s and an E. So first of all, an L would be language be really, really careful and considered about the language you use to talk about change. Think about all the things we’ve talked about, on the context of this conversation, the language is going to be really clear about how you engage with people and how people hear your message, whatever that might be.

On to an E, emotion. Get a temperature check of what the emotion is like about change in the past, change right now change in the future, and try and harness that emotion, if you can, again, that will come back to the language that you use.

And then the other L will be about the loss. Be mindful of any loss that might be read into perceived or actual, you know, real loss that people might experience as a result of the change that you’re proposing or you’re talking about. Name it, be open, be transparent about it. Because until you’ve done that people will not be able to get over that hurdle into a space where they’re accepting of whatever the future state might be.

Katrina Collier 31:35

Yeah, love it. Amazing advice. I could talk to you for another hour, of course. As ever! If people would like to hunt you down to find out more. Speaking of words, that sounds shocking. What’s the best way?

Mark Gilroy 31:55

Please don’t hunt me down because I can’t run very fast, and it’ll be a very short race. I would say you’ll find me on all of the socials @ThatMarkGilroy. And if you want to find anything, find out anything about what we as a company do, what sort of profiles we offer, you’ll find us at TMSDI.com.

Katrina Collier 32:15

Brilliant, thank you so much for joining me, Mark.

Mark Gilroy 32:18

Thank you so much for having me. It’s been a pleasure.

Katrina Collier 32:20

Thank you for listening to The Hiring Partner Perspective unedited podcast proudly supported by the people at WORQDRIVE. Hopefully you really enjoyed what you heard and have left feeling inspired. And if so, I would love your help to create real change. Please pass this podcast on to your hiring leaders and other recruiters and HR, even share it on your social channels, if you feel so inclined. The more reach we can get, the more change we can create. So please remember to subscribe, of course, on your favourite podcast platform. And do come and say hello @HiringPartnerPerspective on Instagram where I share behind the scenes of what’s going on. Until next time, thank you.